Telling Stories (and Making a Point) through Curatorial Practice

Telling Stories (and Making a Point) through Curatorial Practice

by Dr Joshua Y'Barbo

24 Feb 2023

Introduction

Communicating stories and arguments are essential skills you need to learn to become a leader as a curator or creative practitioner, whether working in galleries, museums, or independent spaces. In The Curator’s Handbook, Adrian George’s ‘[…] reoccurring advice through this book is that communication is key’ (2015, p.131.), which can range from managing interpersonal conflicts between artists and colleagues when setting up exhibitions, to telling stories and making arguments through curated content across digital platforms. George (2015, p. 195) wrote that 'Curating is a great deal more than selecting. The curator must be able to engage in creative dialogue – in conversation with artists and the public about art – and stay connected in an ever-growing global network.’ In response to the pandemic, we've seen the curatorial possibilities of working across traditional and digital channels explode with creative responses highlighting the need for subject specialists and theory-in-practice in curation. For example, the website coordinator for the Newcastle Art Gallery, Susan Cairns (2013), stated,

We need expert curators, specialists who have deep knowledge of art history or those who understand how to tell interesting stories with art. We need those with a discerning eye. But we also need curators whose expertise is to connect that which exists in the museum with the broader conversations and information external to it.

This is important because communication plays a crucial part in many curatorial duties, such as collaborative exhibition-making, developing written briefs and statements, establishing ways of working together and avoiding miscommunications with artists and other colleagues. While the mediation of actants through exhibition-making or curating digital content activates different spaces in different ways, such as artworks activating physical and discursive spaces within an exhibition or online narratives.

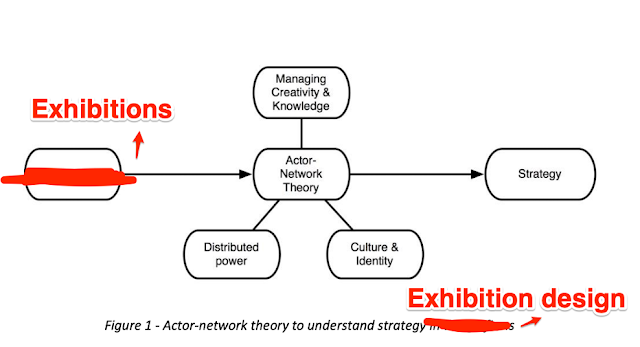

Context: Actor-Network-Theory

In ‘Beyond the Head: The Practical Work of Curating Contemporary Art', Sophia Krzys Acord (2010) wrote, 'Literature in a variety of fields examines the ability of artworks and aesthetic materials to speak, and how this communication is wrapped up in human/non-human interactions and the environmental affordances within physical and/or conceptual spaces.’ But, Acord (2010) focused on actor-network-theory, which:

[…] proposes the term actant, to represent all humans, objects, etc, that come to bear on one another in any given situation of mediation (cf. Callon 1986; Latour 2005). As actants, objects have non-objective consequences for mediation; they do not simply perform the "scripts" they are given. Put otherwise, objects "afford" certain opportunities for use (e.g., a spherical object is easier to roll than a square) (Gibson 1986 [1979]).

So, the artefacts and ideas curators chose to work with have lives to themselves that require advanced knowledge in the arts to understand, which hides the secret lives of artworks away from the unknowing public. By telling stories that contextualise objects, curators have an opportunity to activate artefacts and artworks in a way that teaches the public about their hidden liveliness. Therefore, we’ll discuss how curation might bring actants to life, open up museum collections, and engage audiences in meaningful and personal ways through storytelling.

Curating Collections through Storytelling

In today's session, we'll first discuss the importance of communicating stories and arguments through curation using examples of curating historical and contemporary collections. Second, you’ll complete a 5 min practical exercise you’ll based on your current project before we end with a 5 min group discussion.

Caveats

Today, I'm using both storytelling and the presentation of arguments interchangeably, but not without acknowledging the varying degrees of antagonism that make these two different approaches distinct from one another. I also have chosen to focus on museum storytelling through exhibitions. However, today's session also applies to galleries, independent art spaces, and digital platforms for sharing and mediating content. As a curator, you can choose how, where, when, or why and the channel through which you communicate a story or argue a point. Additionally, there is an incredible amount to cover when thinking about the visitors or audience of your project and how your interpretation might touch something within them that we just don’t have time for today.

Inspiring Audiences to Question Viewpoints

A generalised view of the traditional museum function treats audiences as ‘[…] passive receivers of knowledge’ while storytelling through exhibitions and curated digital content suggest approaches for inspiring audiences to `[…] questions viewpoints which […] have been considered as self-evident’, according to the independent curator and museum consultant Ariane Karbe (2019). Often, curators create a distance between themselves and using their authority to tell stories but scattering interrelated information across spaces or only imply something meaningfully without providing their audiences with the knowledge of a subject they need to ‘[…] form a personal opinion and enter into a “critical dialogue” (Karbe, 2019).

Such a conscious handling of exhibition dramaturgy can be combined fruitfully with other narrative strategies including multiple perspectives, making hitherto ignored stories visible, questioning taken-for-grantedness, visitors’ participation, criticising power structures, promoting empathy and tolerating uncertainty.

A Karbe (2019)

Stories Share Personal Experiences in an Authentic and Easily Accessible Form

Anna Faherty (2023), a teacher and researcher who runs her own content development and digital publishing consultancy, Strategic Content, added that,

Museums are often thought of as places that collect, care for, display and interpret objects. While valid in many ways, this view omits the human element of museums. […] An alternative approach is to think of museums as places that collate and share human experiences. […] Stories share personal experiences in an authentic and easily accessible form. They feel familiar, yet enable us to step into the shoes of others. They are full of detail, but leave space for us to insert our own thoughts, feelings and memories. We use stories to make sense of the world. While we see ourselves in them, it is through stories that we encounter new perspectives that change how we think and feel.

Museum of London’s Collections

Finally, Dr Cathy Ross (nd), past Director of Collections and Learning at the Museum of London, avowed:

We want to engage visitors’ hearts as well as minds. Our exhibition-making is becoming ever-more sophisticated and we know the techniques we should be using: set the scene, show don’t tell, use drama, vary the pace, don’t wander off into boring byways, keep the focus, make sure there is some kind of link between the beginning and the end; take people on a journey.

The Museum of London's collections includes a range of stories from the 1666 Great Fire to London's LGBTQ+, Women and Black histories, and the Olympic Games. This is significant because Karbe, Faherty, and Ross suggest a common problem with meaningfully engaging audiences when curating heritage or contemporary collections.

Curating the Mackintosh Museum Programme (2009 - 2014)

The Mackintosh Museum exhibition programme that ran between 2009 and 2014 provides an example of the challenges faced when curating an exhibition programme within a heritage context. For example, Jenny Brownrigg (2015, p.220), the Exhibitions Director for the Mackintosh Museum at the Glasgow School of Art since 2009, stated:

The challenge for the exhibition programme is to find relevant ways to engage with all the audiences we cater for. It is equally important that practitioners can respond creatively to the building. A past tutor, David Harding [..] often quoted John Latham’s statement to his students: “The context is half the work”.

Pictured: First-floor corridor on the east side of Mackintosh Building between Mackintosh Museum and Mackintosh Room. Completed 1897-1899. Image by the BBC.

Artist Placement Group

Although Harding credited Latham, this quote was actually taken from the Artist Placement Group’s Economic Proposal written in 1965, with Barbara Steveni integral to the founding of APG and developing or co-developing many of the group’s critical principles for placing artists within industries, including the 'Open Brief' and ‘Not-Knowing.’ According to Steveni, ‘As its name indicated, there was no predetermined outcome for the placement. Instead, the intention was for the artist to enter an unknown context and ask questions’ (barnarasteveni.org, nd).

Brownrigg's approach relied on the APG principles to respond to the overwhelming character and tensions offered by the original Mackintosh Museum space, the building and its collection. The context for Brownrigg was the '[…] interaction between past and present', and the '[…] programme had to accommodate the dialectical premise that solutions can come out of potentially opposing forces’ (Brownrigg, 2015, p.221).

A New and Architecturally Opposite White Cube space

In 2014, a tragic fire destroyed the building and library, which required a move to a new and architecturally opposite white cube space. The movement offered new opportunities for addressing a heritage context through the Mackintosh Museum exhibition programme, which is significant because it provides us with an example of a living collection that influences curatorial decisions and public engagement by changing and responding to external factors and random occurrences, like anyone of us.

‘Curating Spaces for Not-Knowing’ by Deborah Riding (2022)

Recent research activities at the Tate provide other examples of changes in curating and collections by applying APG principles to bringing collections to life and engaging audiences through storytelling. For instance, in Tate Papers no. 34, titled ‘Curating Spaces for Not-Knowing’, Deborah Riding (2021-2022) ‘[…] investigated experiences of co-creating knowledge about the museum’s collection.’ Riding explored ‘[…] the context and challenges for both the gallery and its audiences when developing participatory spaces like Tate Exchange’. For Riding, not-knowing proposed, ‘[…] an approach that [could] foster and support the democratic, dialogic and equitable development of new knowledge between Tate and its audiences […]’ (Riding, 2022).

Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum (2018-2022)

Additionally, the Tate’s recent major research project, Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum, ‘[…] focused on recent and contemporary artworks that challenge the practices of the museum’, which gives us another example of using curation to open the museum, invite the public in and make the invisible lives of artworks visible through practice-related research (tate.org, nd). In one of four reports produced for the project, Lucy Bayley (2022) introduces her discussion on the history and theory of curating and collections by stating, ‘When artworks are conceived of as living rather than static, fixable objects they can gain agency in the decision-making process; as philosopher Bruno Latour has said, “objects too have agency”.’

So, we come full circle to Latour, Actor-network-theory, and treating objects and collections as living and dynamic rather than static objects. As both projects suggest, one way of appreciating contemporary art, curation and museum collections' liveliness includes engaging audiences with the stories. Another way is to create spaces that allow audiences to respond to the context of these actants, which traditionally go unnoticed, are unavailable or closed off to the public altogether.

Curation and Exhibition Design Methods: Storytelling through Museum Exhibition Design

Before the exercise, I want to briefly look at a few ways curators can use exhibition design to embrace storytelling in their curatorial practices. In ‘Curation as Methodology', Lindsay Persohn (2021) suggests curation is ‘[…] a transferrable methodology, useful for exploration of aesthetic works as they related to sociocultural histories', which allows us to discuss how we might put curatorial theory into practice when it comes to telling stories and raising arguments. For example, Color Craft (nd), an exhibition design agency, recommends 'museum stories are best told in a linear fashion' that mixes broad and focused information and uses immersive technologies and graphic design when exhibiting and telling stories. As an example of how these approaches appear in contemporary curatorial practice and exhibition, I’ll briefly present a review of the exhibition design of 'Unfinished Business: The Fight for Women's Rights', on display at the British Library in the 2021 Autumn programme.

Unfinished Business: The Fight For Women’s Rights (2020-2021)

In an article about the design approach of this exhibition, Emily Gosling (2020) of CreativeBoom.com wrote:

A key aspect of the show is highlighting contemporary activist groups to encourage visitors to get involved in the ongoing fight for equality themselves. […] According to Margot Lombaert, creative director of Lombaert studio, the exhibition design focuses on creating a "welcoming and inclusive environment, attempting to embody the feeling of movement and activity." Acknowledging the sensitive nature of some of the pieces on display, the site was deliberately designed to include areas for "respite" and "reflection and contemplation," as well as highlighting the sense of collective triumphs and celebrations […] After reviewing the content with the curators we started to imagine a space that spoke of the urgency of the protest march and the ingenuity used to communicate messages through economic means," says Plaid director Lauren Scully. "We wanted the environment to convey the spirit of collaboration and spontaneity – to indicate that this movement is fluid and dynamic, and much larger than can be contained within the gallery walls.

In an example that illustrates Color Craft's (nd) suggestions for museum storytelling, the 'Unfinished Business' exhibition led visitors through history using visual cues and graphic design that progressed events from beginning to end and around significant cultural moments and themes. This exhibition also uses labels and signage to tell the overall story while also telling more in-depth details about specific artefacts, movements, and organisations. This exhibition also incorporated immersive elements, such as audio, video and other technologies, to creatively deliver story elements and rich content that deepen the overall narrative and minute details. Finally, the graphic design of this exhibition creates the flow, sets the tone, and tells the actual story about '[...] the work of contemporary feminist activists in the UK has its roots in the long and complex history of women's rights' (British Library, 2020 that the curator, Polly Russell, wanted to tell to the British Library's visitors and audience.

Exercise

For this exercise, I want you to think about your current project and then tell a story about a struggle in curating historical and contemporary collections you experienced and any lessons you learned.

- Paint the scene: Where and when this story occurs.

- Identify the Actants: People, objects, and texts (representing ideas).

- State the problem, struggle, or challenge.

- Clarify intentions: What ideas, concepts or approaches will you take to address the problem? What are your aims, objectives and intended outcomes?

- Described Actions: What might you do? What or who might you work with? What might actants do?

- Discuss actants: Provide essential details about what or who actants are, how they are used or what they might do, and the messages they convey. Give examples.

- Include surprises: What might you discover? What might work? What might fail? How might artists or audiences react?

- Explain the end result: How and where does your project end? What are the future possibilities? What marks the conclusion?

Conclusion

In conclusion, we should consider how current UAL projects, such as the Decolonising Art Institute and Transforming Collections: Reimaging Art, Nation and Heritage, are changing narratives and telling stories otherwise overlooked and invisible until now. For example,

The UAL Decolonising Arts Institute seeks to challenge colonial and imperial legacies, disrupting ways of seeing, listening, thinking and making in order to drive cultural, social and institutional change. We imagine the Institute as a decentred, disruptive, evolving and porous space.

UAL Decolonising Arts Institute (nd)

Additionally,

Transforming Collections is driven by the belief that a national collection cannot be imagined without addressing structural inequalities in the arts. It will engage with the contentious histories imbued in objects, informed by debates around contested heritage.

T. Payne (2021)

These programmes' work is essential for creating equity and inclusivity within egalitarian art programmes and institutions. I hope today's session inspires you to find your voice and tell stories important to you through your creative curatorial practices. Thank you.

About Dr Joshua Y'Barbo

References

Acord, S.K., (2010). Beyond the Head: The Practical Work of Curating Contemporary Art. Qual Sociol vol. 33. Springerlink. Pp. 447–467.

Bayley, L. (2022). Curating and Collecting. Reshaping the Collectible. Available [online] at: https://www.tate.org.uk/research/reshaping-the-collectible/research-approach-curating-collecting-museology [accessed 23 Feb 2023].

Brownrigg, J. (2015), ‘Contemporary Curating in a Heritage Context’, Gold, MS & Jandl, SS (Eds.), ‘Advancing Engagement; A Handbook for Academic Museums Vol.3’, Museums Etc, Edinburgh and Boston, pp 211-241.

ColorCraft3D. (nd). Storytelling Through Museum Exhibit Design. Colorcraft3d.com. Available [online] at: https://colorcraft3d.com/blog-post/storytelling-through-museum-exhibit-design/#:~:text=Museum%20Stories%20Are%20Best%20Told%20in%20a%20Linear%20Fashion&text=Not%20only%20can%20exhibits%20be,event%20from%20beginning%20to%20end [accessed 23 Feb 2023].

Faherty, A. (2023). Why do stories matter to museums and how can museums become better storytellers?museumnext.com. Available [online] at: https://www.museumnext.com/article/why-do-stories-matter-to-museums-and-how-can-museums-become-better-storytellers/ [accessed 23 Feb 2023].

George, A. (2015). The curator's handbook: museums, commercial galleries, independent spaces. London: Thames and Hudson.

Gosling, E (2020). Designing the 'unfinished business' of the fight for women's rights. Creativeboom.com. Available [online] at: https://www.creativeboom.com/inspiration/designing-the-unfinished-business-of-the-fight-for-womens-rights/ [accessed 23 Feb 2023].

Karbe, A. (2019). How (Epic) Exhibitions Can Tell (Dramatic) Stories. Museumnext.com. Available [online] at: https://www.museumnext.com/article/how-epic-exhibitions-can-tell-dramatic-stories/ [accessed 23 Feb 2023].

Latour, B. (2005) ‘Third Source’, in Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory, Oxford, pp.63–86.

Payne, T. (2021). UAL Decolonising Arts Institute awarded £3m AHRC grant to transform UK collections using emerging technologies. Arts.ac.uk. Available [online] at: https://www.arts.ac.uk/about-ual/press-office/stories/ual-decolonising-arts-institute-awarded-3m-ahrc-grant-to-transform-uk-collections-using-emerging-technologies [accessed 23 Feb 2023].

Persohn, L. (2021). Curation as Methodology. Qualitative Research, 2021. Vol. 21 (1), Sage Publishing. Pp 20-41.

Riding, D. (2022). Curating Spaces for Not-Knowing. Tate Papers no. 34 2021-2022. Available [online] at: https://www.tate.org.uk/research/tate-papers/34/curating-spaces-for-not-knowing [accessed 23 Feb 2023].

Ross, C. (nd). Sophisticated Exhibition-Making: When is a story not a story?. Museum-id.com. Available [online] at: https://museum-id.com/sophisticated-exhibition-making-story-not-story-cathy-ross/ [accessed 23 Feb 2023].

Steveni, B. (nd). Artist Placement Group. Barbarasteveni.org. Available [online] at: https://barbarasteveni.org/Work-APG-Artist-Placement-group [Accessed 23 Feb 2023].

Susan Cairns, quoted in Emma Waterman, ‘Curating the Future’ artsHub, 8 July 2013.

Tate.org (nd). Reshaping the Collectible: When Artworks Live in the Museum. Tate.org.uk. Available [online] at: https://www.tate.org.uk/research/reshaping-the-collectible [accessed 23 Feb 2023].

UAL Decolonising Arts Institute. (nd). Arts.ac.uk. Available [online] at: https://www.arts.ac.uk/ual-decolonising-arts-institute [accessed 23 Feb 2023].

Comments

Post a Comment